urban water

From the dawn of human settlements, water has been a central element in the story of every city. The same holds true for Namma Bengaluru — a land-locked metropolis with no perennial water source, but a site for human settlement since the 9th century (or even earlier) sustained by a unique system of interconnected tanks which sustained settlement, agriculture, and everyday life.

Today, that legacy faces both new and familiar pressures. Rapid urbanisation, shrinking lake systems, and over-exploited groundwater have unsettled natural cycles.

At the same time, Bengaluru is part of a larger global reckoning. Cities across the world — Cape Town, São Paulo, Los Angeles — are grappling with water stress, re-thinking infrastructures to withstand the changing climatic challenges, and rediscovering lessons in both old wisdom and new innovation. From decentralised wastewater treatment to integrated stormwater planning, from neighbourhood-level initiatives and citizens reviving lakes, Bengaluru’s struggles and responses echo and contribute to this global search for resilience.

This page invites you to journey through Bengaluru’s waterscapes — its history, its challenges, and its possibilities — and to re-imagine how the city can chart a path forward toward water security, equity, and resilience.

Bengaluru’s Water: A snapshot

Lakes: 33

Open wells: 49

Rainfall: Up to 1,200 mm

Water source: Rainfall (~3,000 MLD annually), Cauvery river (1,400 MLD)

BWSSB-operated borewells: 14,700

A landlocked city’s waterways

A network of kaluves connecting tanks, allowing overflow from one to feed the next at a lower elevation, preventing floods, conserving water, and supporting life across Bengaluru… And then what happened?

Scroll down to read more

Why wastewater

matters

We generate about 1,950 million litres of waste water everyday of which 76% is treated. Of this, only 30% is reused. What are we missing about wastewater?/ Why should we care about wastewater?

Scroll down to read more

a landlocked city’s waterways

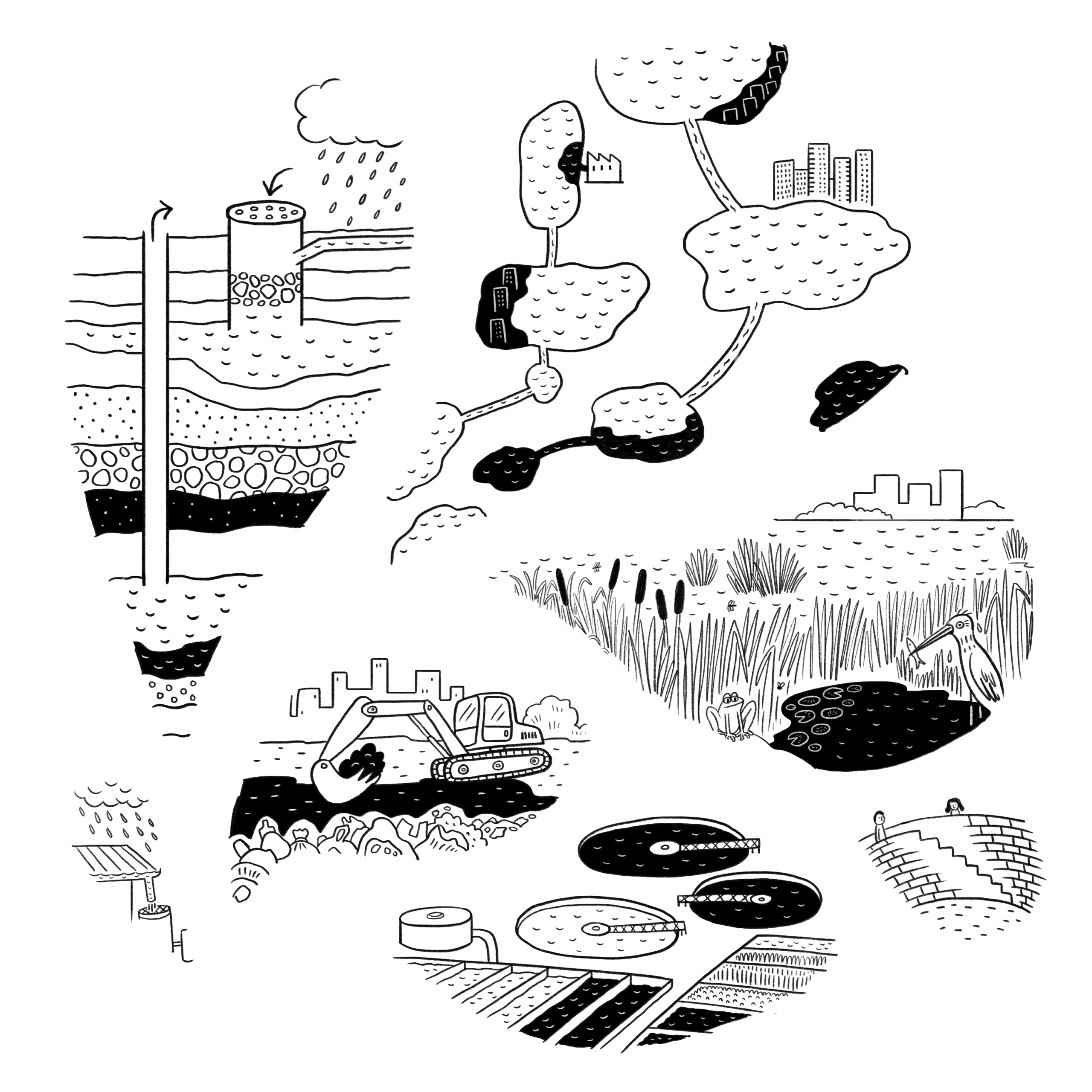

Bengaluru’s relationship with water has shaped its history, geography, and growth. A landlocked city with no perennial river, it has supported human habitation since at least the 9th century, largely thanks to a unique system of interconnected tanks. These human-made tanks relied entirely on rainwater and surface runoff from surrounding catchment areas. A network of kaluves (stormwater channels) connected the tanks, allowing overflow from one to feed the next at a lower elevation – creating a system efficient at preventing floods, conserving water, and supporting life across the plateau.

However, despite its water-savvy design, the city has always struggled with ensuring adequate water supply. In the Great Famine of 1875–77, failed monsoons led to tanks drying up. The city, though, continued to grow in size and population. By 1905, Bengaluru became Asia’s first city to receive electricity, which enabled pumping water from distant sources. Over time, the city began drawing from Hesaraghatta, Thippagondanahalli, and eventually the Cauvery River, nearly 100 km away, 350m lower than Bengaluru’s elevation.

As piped water systems expanded, our relationship with the tank network weakened, both functionally and culturally.

Today, Bengaluru’s demand for water is met primarily from groundwater – a fast depleting resource, the Cauvery river, and only marginally from rainwater and treated wastewater. Despite many civic efforts to revive tanks, most have not yielded a lasting city-wide impact. Why? Because urban water systems must respond to hydrological realities—and Bengaluru’s are complex. Maintaining a functioning, interconnected system of lakes and tanks is crucial to handle the extremes.

why wastewater matters

Wastewater is simply the water we discharge after use, whether at home, in factories, or businesses. It typically is divided into

- Domestic Sewage – This is the wastewater generated from households. It can be grey water – which is discharged from showers, sinks, washing machines, and black water – which includes water with human waste and organic matter discharged from toilets, kitchen, dishwater etc.

- Industrial Effluents – These are wastewaters produced by the different industries in and around Bengaluru, and may contain chemicals, heavy metals, oils, greases, and other potentially hazardous substances.

- Urban Runoff or Stormwater – This is water flowing from roads, rooftops or other impervious surfaces and can carry sediments, heavy metals, oils etc.

The rapid pace of urbanisation, industrial growth, and population expansion has led to an exponential increase in the generation of wastewater in Bengaluru. While the term ‘wastewater’ denotes a byproduct that cannot be used and is hence seen as ‘waste’, it is rapidly being accepted as one of the most important elements in meeting the water needs of growing populations across the globe.

The city generates approx. 1,950 MLD (million litres/day) of wastewater, of which 76% is treated. Of this, only 30% is reused. As this issue gains prominence, it becomes imperative to examine the challenges associated with wastewater management in Bangalore and explore sustainable solutions to ensure the city’s water security and environmental well-being.

One of the primary issues is the inadequate sewerage infrastructure, resulting in the discharge of untreated sewage into water bodies. The industrial sector, too, contributes significantly to the problem, with many units releasing effluents without proper treatment. Encroachments on stormwater drains exacerbate the issue, leading to the contamination of both surface and groundwater.

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges around wastewater lies in shifting the mindset that wastewater is not usable even after treatment. In reality, the level of treatment depends on its end use: agriculture, industry, or non-potable domestic purposes each require different standards. Nowadays advanced treatment processes, including membrane bioreactors, constructed wetlands, and decentralised wastewater treatment systems are being deployed to treat wastewater in the city. The Koramangala-Challaghatta (KC) Valley project, in which the government plans to fill 134 lakes at the cost of Rs 1,342 crore, is one of the first in India to formally use secondary treated wastewater at significantly large volumes to fill the tanks and river ecosystem and provide water for agricultural use.